A space at the end of the road | ethnographic experiments in ecofeminism

or ‘sensory polemics in auto-ethnography,’ perhaps

a real and imagined scrappy space for rough drafts, installations, drawings, prints, recordings and soundscapes, flash nonfiction and poetry, why not

Thinking with:

Kathleen Stewart | A Space on the Side of the Road: Cultural Poetics in an “Other” America

In her ethnography A Space on the Side of the Road, Stewart approaches West Virginia as a narrative space that “stands as a kind of back talk” to America’s “mythic claims to realism, progress, and order.” This “space” is as much epistemological as it is imaginary, as it is real. Her ethnography:

Tells its story through interruptions, amassed densities of description, evocations of voices and the conditions of their possibility, and lyrical, ruminative aporias that give pause.

I center a space of urban territory in Philly likewise - to situate an embodied creative practice of writing and making and breaking and reckoning and back talk to fascism.

Joanne Barker | “Territory as Analytic: The Dispossession of Lenapehoking and the Subprime Crisis,” Social Text (June 2018): 19-39.

In this piece, Barker addresses the coproduction of US imperialism, racism and debt in the “dispossession and indenture of Indigenous peoples,” with a focus on the fraudulent dispossession of Lenapaehoking, including the Walking Purchase which defrauded Indigenous people from the very parcel of land I am currently writing about/with. Understanding “territory” as an analytic positions Indigenous dispossession as formative to US empire and to contemporary economic disparity for Indigenous people and others who are “indentured within/to the state.” Barker argues that any anti-imperialist movement demands a reckoning of “territory.” Lenape stories embed values about territory, including “individual and collective responsibilities to and between multispecies and the land on which we live together.”

Audre Lorde | The Cancer Journals, A Burst of Light & Zami

My dog-eared copies underlined in multiple colors from many rereads recently dusted and cracked open anew. I have not been able to hold them since my beloved friend and LGBTIA+ activist Gloria Casarez died from breast cancer.

“The machine will try to grind you into dust anyway, whether or not we speak.”

“For those of us who write, it is necessary to scrutinize not only the truth of what we speak, but the truth of that language by which we speak it.”

“What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?”

Derek Jarman | Modern Nature

Jamaica Kincaid | My Garden Book

Sara Ahmed | all things

Thinking about:

marginal, in-between spaces | places | people and what thrives therein

refusing presumed measures

collectivity | mutuality | mutual aid

land | terrain

being in-place, being emplaced, multi-sensory embodiment

What Anna Tsing calls “friction” and Kathleen Stewart describes as “what being rippled by the minute can do for our attention to ecologies.”

What the Institute of Queer Ecology calls “critical optimism” or a “coping mechanism for the pain of living in, engaging with, and loving a biodiverse world that is being undeniably annihilated.”

Lauren Berlant’s term “cruel optimism” to explain how we hold onto what diminishes us (the false promises of capitalism? the false promises of heteronormative happiness? the violent beliefs in individual accumulation and prestige?).

Milton Almonacid’s imperative that westerners reject “happiness” as a naive construct, its pursuit always at the expense of something or someone else.

“de-growth” (Almonacid) and the “feminist snap” (Ahmed): breaking bonds with what and who diminishes us

“The question I ask, over and over, is who is profiting from this?” - Audre Lorde

local and inter/national legacies of settler colonialism, forced displacement of Indigenous people and lifeways, immigration, the Great Migration, (de)industrialization

Palestine, Gaza

climates | ecosystems

mycelium as methodology

biodiversity | endemic and invasive

decay | swamps | carbon | brackishness

“the americas” | Mayan & other healers I know, restoration, reparation

bounties versus hoards

fugitive geographies, fugitive methodologies

nonbinary existence, growth

desynchronizing from linear time as decolonization

feminism/s and ecofemisms

haunting/s

“Someone needs to explain to me why wanting clean drinking water makes you an activist, and why proposing to destroy water with chemical warfare doesn’t make a corporation a terrorist.” - Winona LaDuke, as quoted by Jason Clark in text about his piece Winona and the Big Oil ‘Windigo’ exhibited as part of Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always.

In her book The Serviceberry, Robin Wall Kimmerer explains that Windigo, in Potawatomi culture, is the cannibal who suffers from the illness of taking too much and sharing too little, from valuing individual consumption above community thriving, from turning collective goods into commodities.

BLOODROOT

I shut my eyes. Chuff my hands, dirty from planting trout lilies and trillium, bloodroot and jack in the pulpit—sweet talking spring ephemerals to coax them elsewhere. Dark dark dark comes and the train pitches by with its rust sounds and clouds. Quarter moonlight and early night is too tight with too soon and too hot breathing. It’s coming, the panting of summer, hotter than it need be, than it should be. Hurry hurry. The tricked out cool blue lights of a trike motorcycle rolls by, some sort of 60s soul haze of notes drags behind it, and I pause, shovel in hand. Sweet hot spring in the city.

Aptly named, bloodroot is a native perennial that seeps red-orange sap when its roots are cut. Bees and other insects pollinate it, but bloodroot can self-pollinate if necessary. Once pollinated, it produces elongated pods that, when ripe, scatter seeds that attract ants. Ants in turn disperse the seeds when they carry them home for snacking.

For humans, the roots are handy for dyes and body paint, and to ease many conditions, including for menstrual health and as an abortifacient.

Plant-knowledge comes best from observation, from respect, from knowing that a plant has many necessary functions beyond human ones and that these in turn protect collective habitat. The human use a of plant, in my mind, is also a chosen exchange between plant and animal in which human bodily autonomy—the ability to choose what we put into our body and/or what we decide to keep in our body—is assumed.

In PA, in Lenapehoking, in this age of vitriolic violence against women, nonbinary and trans bodies, bloodroot blooms and abortion remains legal. Like bloodroot, however, (legal) access to abortion and to body autonomy depends on its defense; it relies on pollinators to remain robust, even though, if need be, it will self-pollinate to support rhizomatic growth underground. Rhizomatic growth does not obey state borders. Our current regime will stop at nothing to criminalize those who seek and provide abortion and other forms of heath care within and across state line. Criminalizing and defunding maternal health care endangers lives. Media campaigns spew pollution through misinformation and women are dying and being prosecuted for claiming given bodily autonomy.

How to learn about actions and attempts to eliminate and limit access to sexual health care.

Bloodroot vegetarian restaurant and bookstore in Bridgeport, site of one of my first encounters with feminist collectivity when a teenager (thanks JB)

Auto polyvocality, huh

If autoethnography can be multimodal, can I, alone, be polyvocal? I write across projects into overlapping and adjacent field sites, into neighborhoods that adjoin, into communities that span neighborhoods, into the neighborhood where I also live, into the communities that are also mine. When I write ethnography, I am also writing autoethnography. My role as an applied researcher ebbs, shifts across spaces and encounters, as does my relationships to my neighbors, who are also my collaborators.

This site, this space, is part of the venn diagram of my field work. It is also within sight of my home. I throw questions from here and they hurl through field and home and back like a boomerang to the head. They land here, they space out here where I bring my shovel and my recorder. Where I court the foxes. Foxes thrive in ecotones, in-between transitional spaces, like this scrappy triangle between rail, bus, parkway and parkland. Where I scooped up a handful of bullets one day in November. I wrote this while in the field today which means I wrote this while out in my community today. As a rule I don’t write poetry. Never have. But it was a poetry workshop after all.

A cop / a table of cops / a table of uniformed cops / write poetry

A community poet shares verse about a boy

A boy

A boy

A fifteen year old boy

A fifteen year old boy, a child

A fifteen year old boy, a child shot killed left for dead on the grassy apron of his school

A few blocks from where we sit

A few months from where we sit

from where

A table of cops listen / to the out breath of verse / their guns at rest, for now

Devil’s Walking Stick

Among other alarming actions, this week:

IRS agrees (cooperates? capitulates?) to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

The Supreme Court upholds the deportation of Venezuelans, citing the 1789 Alien Enemies Act while students from Muslim-majority countries continue to have visas revoked

3 of 4 branches of the Division of Violence Prevention eliminated

All staff working on intimate partner violence prevention and sexual assault prevention dismissed

Most of the CDC’s Division of Reproductive Heath laid off

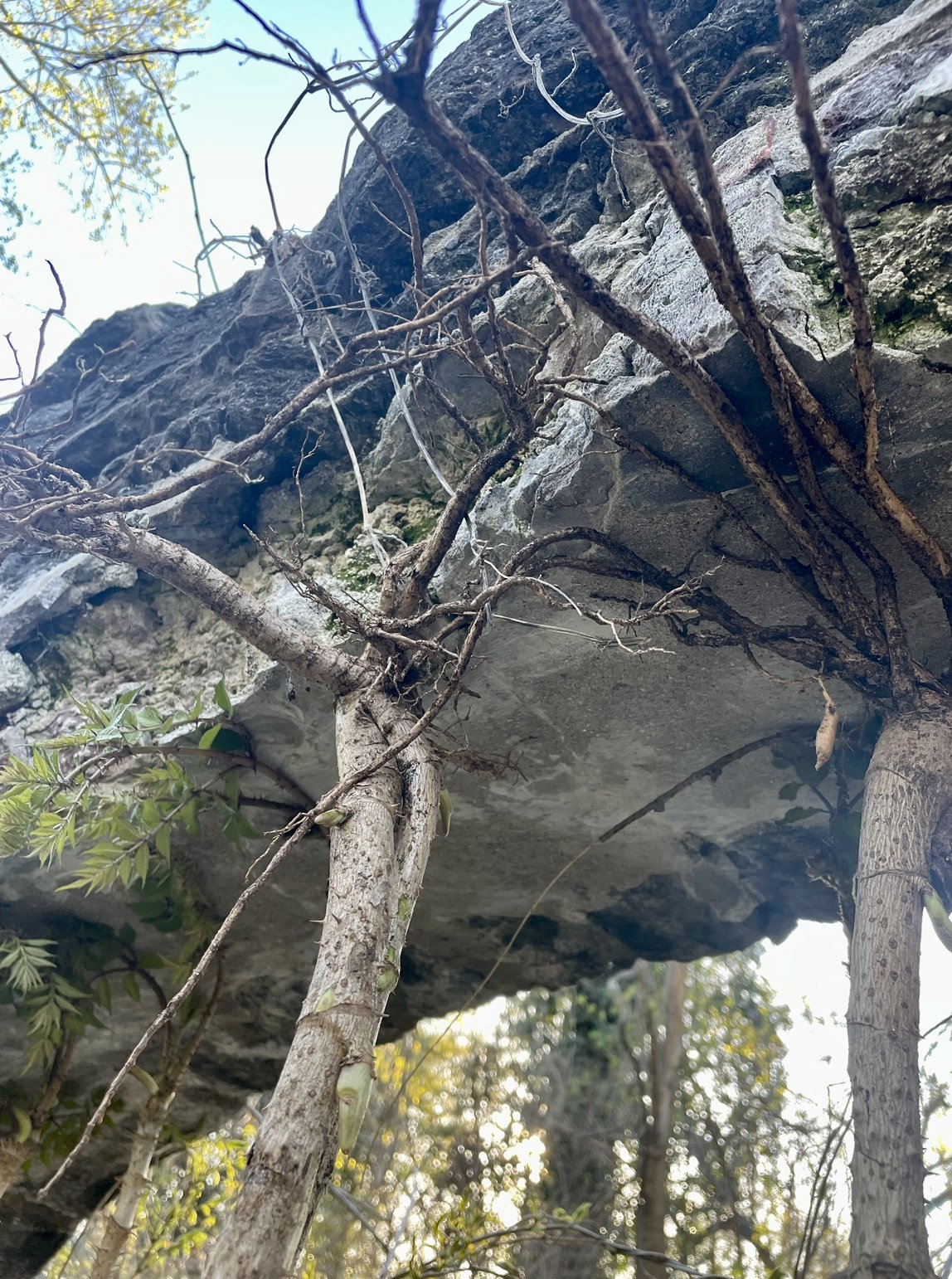

Thorns rip my hands until I put on gloves; they rip my gloves. Uprooting aralia elata, not to be confused with aralia spinosa, devil’s walking stick. Turning roots upside down to make window bars. On the nose? Yes. AND. The current US administration is mostly white men with documented histories of sexual abuse. They are not behind bars. Thinking about: bars on the windows of the domestic violence shelter where I worked for five years. The crisis hotline there that never ceased ringing. I would hear it in my dreams. Sometimes it rang me out of sleep and into a crisis, a literal matter of life or death. The years I facilitated peer sexual assault prevention education and accompanied assault and rape survivors through police and hospital encounters. The years I provided counseling and resources for sexual and reproductive health. The years I worked as researcher on studies that value women, that save lives. The women and children I met and knew and loved; the ones that didn’t make it.

Mahmoud Kahlil. Behind bars in an Ice private “detention facility” in Louisiana. In his words: “My arrest was a direct consequence of exercising my right to free speech as I advocated for a free Palestine and an end to the genocide in Gaza.”

I turn with sticks thorn-ed to my gloved hand. The devil is in the details. She asks if this is the end of the road. I gesture vaguely with my bouquet of rage. Sure. End of the road. Beginning of the road. What do I know? She has to walk, she says, because of this new dog leaping at the end of the leash. It has one blue and one green eye. Her sweatshirt says ‘Little Saigon’ and I Philly-love her for it. Watch for the foxes, I say as she pushes away, meaning: foxes, watch for this dog. She does not seem to notice that I’m making window bars with thorns in the old foundation.

He asks, does the trail end here? I gesture around. Sure. End. Beginning. Wtf and why would I know? Jeezus, what is with these end of road-ers today? He doesn’t notice my hand clippers or the rooty sticks paused on their way to join the others.

In parts of eastern North America, devil’s walking stick is native but is often confused with its close relative, the species aralia elata, native to eastern Asia and brought here sometime in the 1830s. Here, in this space at the end of the road, along the rails and among the fox holes, we find aralia elata but it’s really hard to distinguish it from its devilish cousin. Either way, both plants are edible. From art, from rage, from their temporary installation these roots will become a sauteed delicacy. In parts of Asia, people cook and eat the tender crowning leaves of Aralia elata in early spring. In Korea, for example, it is called Dureup. According to bburi kitchen, “Dureup can be eaten like blanched asparagus: Simply blanch in lightly salted water, and enjoy with your preferred sauces. Here in Korea we dip it in cho-gochujang (초고추장, vinegared gochujang). You can also make a jeon, or savory pancake with dureup: coat in a simple flour and egg batter and pan fry. We also eat dureup twigim (튀김, deep fried), and rice cooked with dureup.”